At the beginning of the pandemic, just over three years ago, Google Analytics showed a huge increase in the amount of traffic generated from baking and cooking at home. You can see in the graph below that sourdough reached its peak popularity on Google searches just as the pandemic was gripping the nation. It makes a lot of sense too; people were desperate to find things that they could complete entirely in their homes, especially those that could reduce the number of items that were on a grocery shopping run and potential exposure to this new virus floating around. Now, sourdough recipes are appearing all over the internet, with burgeoning food blogs displaying their new bakes’ beautiful designs and perfect pairings. But what is happening behind this explosion of sourdough in the kitchens of the home baker? We’ll delve into the science of what gives sourdough that distinct flavor and some tips on how you can get started at home yourself.

Starting Starters

Sourdough contains a very simple set of ingredients: flour, water, and salt. That’s it! For a loaf that tastes seemingly so complex, the process requires a very small amount of input factors. However, sourdough’s leavening factor makes it unique. Rather than using a typical commercial yeast that you can buy from any grocery store, sourdough utilizes a fermented culture of flour and water, also known as a starter. This starter begins with equal parts flour and water by weight (it’s recommended that you use unbleached flour, such as the King Arthur brand to avoid any possible issues with starter forming) that comes in contact with natural yeast.

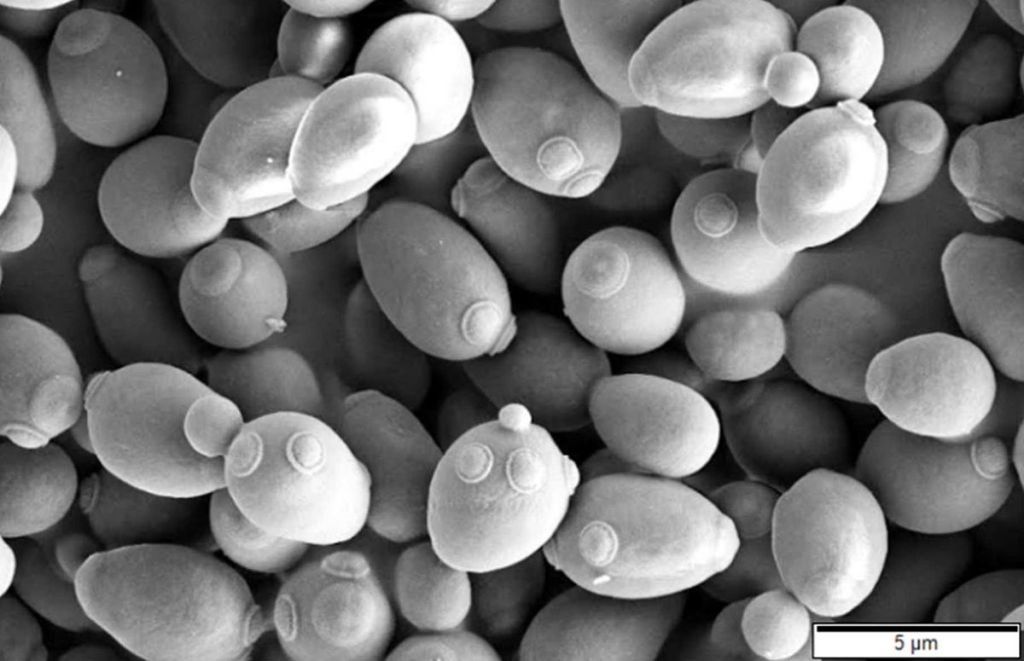

***Natural yeast, also known as wild yeast, are natural multi-micro flora that becomes seeded in a dough that has been left exposed. These are the basis of starters and bread across the world, as the yeast that generates in a starter dough is typically the same worldwide. Most yeast in these starters is a strain of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae, with some other yeasts and lactic acid bacteria. These varieties of organisms that exist with S. cerevisiae are typically what give the sourdough its flavor. Lactic acid bacteria give sourdough a yogurt like flavor, while acetic acid-producing bacteria give it more vinegary notes**

Natural yeast are single-cell organisms that are incredibly useful in baking and fermenting projects, as they break down the sugar and starches in dough and convert them into carbon dioxide and ethanol. They are also what give beer its bubbles and alcoholic content. The yeast converts the sugar into carbon dioxide and ethanol through a process called anaerobic respiration, which means that it does not need oxygen in order to complete the reaction. Glucose, or the sugars present in the flour, are broken down by glycolysis (literally meaning “sugar decomposition”) which produces 2 carbon dioxide molecules, 2 alcohol (ethanol) molecules, and 2 energy molecules. The process is written below in scientific notation:

C6H12O6 → 2CO2 + 2C2H6O + 2ATP

This is why when we watch our starters grow and form over the first couple of days, we begin to see bubbles form and pop throughout the mixture. Carbon dioxide is formed via the yeast’s breakdown of the sugars and starches. The starter can also begin to form the ethanol that comes from the reaction in large enough amounts to be seen. This is called “hooch” and means that your starter needs to be fed again. While it wouldn’t be the worst thing to ingest the hooch that is coming from your starter, it is recommended that you pour off any hooch that has formed before feeding your starter again. But that is getting ahead of ourselves.

For an easy starter, mix sixty grams of unbleached flour and sixty grams of warm water, about one-half cup and one-quarter cup, respectively. Mix the two ingredients until it becomes smooth and thick. Cover the mixture in plastic wrap or a lid if mixing in a jar and let sit in a warm spot for around 24 hours. After this time, this is when we are inspecting for the bubbles mentioned earlier: we want to make sure that our starter has begun to ferment, which is indicative of yeast having come in contact with our mixture. Rest the mixture for another twenty-four hours, and don’t worry if there are not any apparent bubbles. Sometimes starters need a bit more time, especially depending on the type of flour you used to start. After day two, this is when we typically see the presence of hooch. Again, this means that our starter is “hungry” and needs to be fed again. Remove around half of the mixture in the vessel you are using and replace it with a “feeding” of sixty grams of flour and sixty grams of water. It will begin to rise and create more bubbles throughout the culture, and once its falls, it is time to feed the starter again. Usually, after a week from beginning the process, the starter will be doubled in size and its texture will be spongy and soft. It also should begin to smell a bit like yeasty bread. If it smells like alcohol (or some describe it as stinky feet), it means that your starter is underfed and needs some new flour. If all is well, your starter can be transferred to a new clean dish and you are ready to bake!

***NOTE: Some starters can be ready in a week, while others can take up to ten to fourteen days to complete. Once you have seen the activity begin to diminish and the texture is described as above, your starter is ready to use***

Anatomy of Bread

Sourdough and other breads all have the same anatomical structure: crust and crumb. The crust is formed as the starches in the dough begin to absorb moisture from within the bread and the oven atmosphere. As they gain more moisture, they eventually reach a breaking point, liquifying the starch and becoming a gel on the outside layer of the bread. A higher moisture content on the bread surfaces directly correlates to a crisper crust, as there is now a larger quantity of this starch gel on the bread. The caramel color of the crust comes from the Maillard Reaction, which was talked about more in-depth in an earlier post. The rigidity of the crust also comes from the coagulation of gluten molecules (which before was what gave bread its elasticity).

The crumb is the interior of the bread or anything that is not the crust. The water and flour that are used throughout the baking process are the greatest determiners of the final crumb structure. In the initial mixing, gliadin and glutenin (proteins available in the flour) combine to create the gluten that helps trap gases during the baking process. The more available gluten means a higher likelihood of entrapped carbon dioxide within the viscoelastic structure of the bread. The particular carbohydrate fermentation that occurs to provide this carbon dioxide is called the tricarboxylic acid cycle. The equation for fermentation is the same as the one listed above. Fine texture crumb is described as thinner walls between the open cells of the bread, while coarse is for larger cell walls. Breads that have higher water contents or lower salt contents are likely to experience very large cells, like a Swiss cheese slice.

Flavor Development

Flavor development of a sourdough loaf occurs at all stages of the baking process. The types of flour, whether rye, whole wheat, barley, or more, can impart the particular flavors that accompany those whole grains. Buckwheat flour makes a vinegary starter, whereas amaranth flour is toasty, and sorghum is a more fermented, yeasty smell. You can also have a drastic change in the sourdough flavor based on the bacteria that become entrapped in the dough during the initial starter phase. Starters with lower water contents, also known as “stiffer starters,” can encourage the lactic acid bacteria to create a sharp acetic acid taste, similar to vinegar. Higher water content, or runnier, starter? The lactic acid bacteria give a smoother, creamier tang to the bread compared to the sharp acetic acid. Fermentation of the starter in a warmer kitchen makes lactic acid bacteria create a sourer dough, but cooler temperatures (like storing your starter in the fridge) allow the yeast to produce a fruitier flavor.

Sourdough has been around for thousands of years, as the natural impregnation of yeast in sitting doughs has been taken advantage of since the times of the ancient Egyptians. With the more recent boom during the beginning stages of the pandemic, it has shown that we don’t need to always be buying a jar of yeast from the store in order to make delicious, fresh bread in our kitchens. Sometimes, with just a little flour, water, and salt, we can make science into tasty and beautiful creations.